- Congregation Beth El–Keser Israel

85 Harrison Street, New Haven, CT 06515-1724 | P: 203.389.2108 | office@beki.org

85 Harrison Street, New Haven, CT 06515-1724 | P: 203.389.2108 | office@beki.org

Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel (“BEKI”) formed from the merger of Congregation Beth El (founded in 1892 as Bnai Israel) and Temple Keser Israel (founded in 1909). Both predecessor congregations were in the City of New Haven.

With its recent growth in membership, it is quite probable that most of the newer members, including some of the most active leadership, are not aware of the varied history of what is now Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel. In June 1985, the Congregation celebrated the 25th anniversary of our building. A banner was stretched across Whalley Avenue and the building was wrapped with a giant blue bow. A large banquet was held in the social hall, and a commemorative ad book was published. In preparation for the event the general Chairman, Paul Goodwin, asked me to research and write the history of the Congregation. An adaptation of that history follows. Part of this history is adapted from the work of Rabbi Elliot B. Gertel. — Alan Gelbert, et al.

According to Jews in New Haven (vol. 2), edited by Dr. Barry E. Herman, published by the Jewish Historical Society of Greater New Haven, several Jewish families in the Congress Avenue, Washington Avenue, Commerce Street and York Street area felt the need to establish an additional traditional congregation in the late 1800s.

The existing synagogues were already overcrowded. In 1891 they formed a group for the purpose of worship and study, praying in private homes and hiring a teacher for their Chevra Mishnais (Mishna Study Group). In June 1892, the group purchased land for a cemetery in Hamden’s Highwood section under the name ‘Chevra Benai Israel.’ Articles of Association were filed with the State of Connecticut on July 1, 1892 as the Congregation Benai Israel.

The Congregation purchased a house at 10 Rose Street in 1894, and built a new building during the winter which came to be known as the “Rose Street Shul.” Dues were 10 cents per member household per week. In 1901, under financial stress, the group reorganized as “Congregation Beth Hamedrosh Hagadol B’nai Israel.” It was the largest traditional congregation in the area for many years.

The building itself was box-like. The exterior of buff-colored brick had some fancy masonry over the doors, windows and stained glass star of David. The interior was bright and spacious, with a center-located bimah. A gallery for women encircled on three of the four walls.

Membership dues were low, but the shul was filled more by ticket buyers than members at holiday time. Aliyot were auctioned to the highest bidder, cantors were hired just for the High Holy Days — the more renowned the cantor, the better the ticket sales. The Rabbi did not have a contract with the Congregation. By informal arrangement, he would be available to one or more congregations to deliver sermons, but earned his living by providing personal services such as weddings, funerals and supervising shehita (slaughter) of animals for kosher meat. Rabbi Aaron Shuchatowitz began his service as the Congregation’s rabbi in 1935. Mr. Louis Friedman became its shamash (ritual director) in 1946.

By the 1940s and the end of World War II, a second generation, American born, had come along. Post-war prosperity had prompted movement away from the geographic area of the shul, and attendance at Rose Street was decreasing.

In 1955, under the administration of Mayor Richard C. Lee, the City of New Haven began a program of redevelopment. One of the first in the country, New Haven was named a “Model City.” The goal was to eliminate blighted areas and restore commercial vitality to the downtown section.

A major thrust of the redevelopment program was the Oak Street Connector, a multi-lane highway connecting to and from the Connecticut Turnpike. This would pass through the heart of the so-called “Jewish Ghetto.” College Street was to be extended over the highway to Congress Avenue, passing but yards from the site of the synagogue.

In October 1955, the Congregation received a letter from the City about acquiring the building. Paul Goodwin was asked to represent the Congregation in this matter. He had worked with Dick Lee in veterans’ organizations after the war. His committee included Dr. Samuel Gelbert, Philip Magid, Robert Shure, Louis Goodwin, Edward Weinstein, Charles Byer, Edward D. Goldman, David H. Levine, Edward I. Levine and Abraham Alderman.

The first figure offered by the City was $92,000. Edward Weinstein, while running a large grocery business on Dixwell Avenue, was nevertheless a Yale graduate engineer. It was largely through his efforts that the value of the building was augmented to the final price of $203,000.

The committee had taken a survey of the membership and determined that most of the members now lived in the Western section of the city. It was pointed out, however, that those members who remained in the area of Rose Street would not ride on the Sabbath; therefore, the City would have to make available property in the area on which to build a small synagogue for them. The committee had thus recognized and accepted the responsibility to build two synagogues.

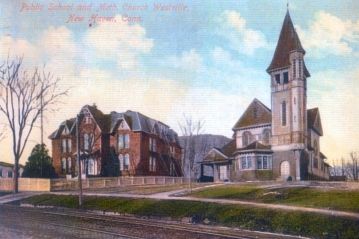

The City offered a parcel of land of 7,000 to 9,000 square feet on Congress Avenue for the downtown synagogue. In Westville, the Benton School property at the corner of Whalley Avenue and Harrison Street was offered. The latter was a beautiful site at the crest of a hill with West Rock as a backdrop, across the street from the Mitchell Library and next door to the Westville Methodist Church. A right of way was negotiated for access to the church from Harrison Street and for parking on Sunday.

The last services at Rose Street were held on Sukkot of 1957. Arrangements were made with the City for the use of a room in the Cedar Street School until the small synagogue could be built. These services were conducted by Mr. Friedman and Rabbi Shuchatowitz. Before the acquisition of the Westville property, all synagogue meetings also took place at the Cedar Street School. High Holidays services in 1958 and 1959 were held at the Jewish Community Center on Chapel Street.

The Congress Avenue property, as it turned out, was coveted by Yale University for future hospital expansion. Yale offered the Congregation a swap for a larger parcel on Howard Avenue. This deal had to be approved by the City Council and the Yale Corporation and was not finally approved until March 1960. Yale retained an option for first refusal on the second parcel.

The first plans to be drawn were for the small synagogue, a basic building to house 50 to 75 people at an estimated cost of $75,000. The majority all along intended to build a downtown shul. It was anticipated that it would one day be the only traditional synagogue in the area and would serve many people on their way to and from work, for Qaddish and for daily services. No action was taken on building because of the delay in acquiring the property.

Meanwhile, the Benton School property had been acquired. Dr. Herbert Winer, led a crew of men who rehabilitated the yellow house on Harrison Street to serve as a temporary synagogue, school and rabbi’s office. Martha Goldman was tireless in organizing the religious school. Joan Gelbert was the first Sunday School teacher. A nursery school was also organized, under the direction of Gloria Dubrow, assisted by Ethel Goldberg.

A survey of the membership showed that those who intended to go to the Westville site preferred mixed seating (also known as family seating). As it was felt that Rabbi Shuchatowitz was not inclined to adapt to this arrangement, Rabbi Isaiah Rackovksy, who had served in the US Army with Robert Goodwin and was well-known to him, was interviewed and found to be learned and well-spoken. Rabbi Rackovsky, who had Orthodox semikha (ordination), did not object to the mixed seating, which was becoming the practice of many Orthodox and most Conservative congregations by that period. Rabbi Rackovsky moved to New Haven with his wife and son and assumed the pulpit of B’nai Israel.

The hiring of Rabbi Rackovsky set up a situation that pitted these two men against each other for the leadership of the Congregation. Rackovsky was now the contracted rabbi for all of B’nai Israel and Rabbi Shuchatowitz was the loser. However, he maintained a strong following in the downtown group.

The General Meeting of the Congregation on 28 June 1959 authorized the expenditure of $325,000 to build the synagogue on Harrison Street in Westville. The downtown group grew restless with doubt that the small downtown building would ever be built. Perhaps they feared there would not be enough money, or perhaps they were fueled by the rivalry between Rabbi Shuchatowitz and Rabbi Rackovsky. Meetings grew heated with personal attacks. Long-time friends became bitter enemies. Overtures by the White Street Synagogue to absorb the B’nai Israel downtown remnant were discussed in committee, and while it appeared favorable, the downtown group refused to attend the meetings.

When the plans for the Westville building showed a one-floor sanctuary with no separation of men and women, the leaders of the Congregation were enjoined with a lawsuit and personal attachments. The basis of the suit was that B’nai Israel was chartered as an “ultra orthodox” Congregation and as such could not have mixed seating.

The downtown group was represented by attorney Robert Berdon, and the Westville group by attorney Louis Feinmark. Before the case came up in court, construction was completed and B’nai Israel Synagogue at Whalley Avenue and Harrison Street was dedicated on the weekend of 24-26 June 1960. (See the Dedication Program.)

The presiding judge recommended that the suit be heard by a court-appointed referee who would return a recommendation to the judge. The referee was retired Judge Patrick B. O’Sullivan. The plaintiffs presented “expert” testimony by learned rabbis that separate seating was the rule in Orthodoxy. Although mixed seating was allowed in many Orthodox congregations until the 1980s, it had never been endorsed by the Orthodox rabbinic organizations. It remained for Rabbi Rackovsky to vindicate the position of the defendants. But the day before he was to take the stand, he was visited by Orthodox leaders from New York who impressed upon him the negative consequences to his career of testifying that mixed seating was acceptable in “orthodox” congregations. Rabbi Rackovsky announced that he was unable to testify. This prompted Judge O’Sullivan to recommend that a settlement be sought.

Cantor Jordan Ofseyer

The minority faction, ultimately representing about a dozen families, was given the Howard Avenue property, the Aron Qodesh (Holy Ark) from Rose Street, a number of cemetery plots, and $30,000 less certain pledges, to be paid over a period of 17 months. They also retained the right to the B’nai Israel name. In the aftermath, Rabbi Rackovsky’s services were terminated in April 1961. The remaining 170 families on Harrison Street reorganized as “Congregation Beth El.” B’nai Israel ceased meeting for religious purposes after they had to leave the Cedar Street School, and the Howard Avenue building was never built. The assets and name of B’nai Israel were taken by what is now known as “The Westville Synagogue,” a nearby Orthodox congregation, in 1974. While its funds and original name were lost, the Beth El group retained most of the member families, a sense of communal continuity, memorial tablets, and Mr. Louis Friedman.

Cantor Jordan Ofseyer was engaged to conduct the High Holy Days services of 1961. The members liked the young man and he continued to serve on weekends until completing his rabbinic studies the following June. He was formally installed as rabbi at a ceremony on Friday night in December 1962. The installation address was given by Dr. Mordecai M. Kaplan. At that time, the congregation comprised 230 families. During Rabbi Ofseyer’s eight-year tenure, Ezra Academy, a Solomon Schechter Day School, was organized and held classes at Beth El until it its growth required it to find larger quarters. In January 1967, Congregation Beth El formally joined the United Synagogue, for the first time officially identifying as a Conservative synagogue.

In 1909 a small group of Jewish families who had settled in the Dixwell Avenue neighborhood dreamed of a Temple to be the focal point of their community. The handful of families purchased a building on Foote Street and Temple Keser Israel was born. Rabbis who served the congregation included Rabbi Joseph Freedman (1940-1942) and Rabbi Morris Schnall (1942-1945).

Rabbi Leon Spitz

Over the years, the dream of growth came true and the Foote Street building could no longer contain the congregation. In 1945 Keser Israel joined the Conservative movement, and invited to the pulpit Rabbi Leon Spitz, a graduate of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Rabbi Spitz was a scholar and a man of great organizational ability.

In 1948 Dr. Frederick M. Pashall, who served as president for a decade, along with committee chairmen Abraham Gubin, Isadore Miller, Herman Paul and Nathan Sosensky, began a fund drive. They sold the Foote Street building and purchased the Norton Street Congregational Home. Unexpectedly, however, the Plymouth Church on the corner of Chapel Street and Sherman Avenue was put up for sale. The president, assisted by Louis Scherban and Goodwin D. Wolff, purchased the building in the name of Congregation Keser Israel for $138,000 (about $1.35 million in 2015 dollars).

The building seemed to have been made for Keser Israel. It was half fortress and half enchanted castle. No two walls were the same, no two towers identical. It was an imposing palace, but somehow off-beat, heimish (warm). It did not overwhelm the congregation, but gave it a personality, a sense of being at home in its own special home. The congregation took its time to settle into that home. Abraham Gubin, Louis Scherban and Samuel Smith traveled all around, looking at synagogue sanctuaries, in search of ideas. Jack Levine supervised the decoration of the main hall, in which there emerged an ark and bima that seemed to have belonged in that old building all along.

By 1951 the congregation was ready to formally dedicate this new House of Worship. Rabbi Spitz, the “Altar Builder,” as he was called, had left for a “fine Philadelphia Congregation.” A new rabbi was brought in to be installed at the same time, to be consecrated to Keser Israel together with the friendly castle: Rabbi Andrew Klein, whose warmth, rapport with children, and ecumenical spirit were to become legendary in New Haven and beyond.

Minutes of the Board of Directors meetings show that talks of merger of Beth El and Keser Israel date as far back as 1960, mostly between individual members. However, when official committees were appointed, they never got very far. Beth El held merger talks with both Beth Sholom in Hamden and Keser Israel in 1962. These were stalemated.

On the surface, merger seemed a natural thing when official committees were again appointed in 1966. Both congregations had their troubles. Beth El’s growth was steady, but there was a large financial overhead of the building, new school wing (1964) and staff. Keser Israel had experienced a decline in membership of younger families with children in the religious school. (Keser Israel total membership: 1948, 350 families; 1961, 278 families; 1965, 271 families; 1968, 259 families.) The main stumbling block was finding a financial arrangement that was acceptable as fair to both sides. Beth El had gone through a Building Fund campaign and felt that new people should not come in through merger without some financial contribution beyond the value of their synagogue property. The figure they set was not acceptable to Keser Israel and negotiations were again broken off.

Rabbi Andrew Klein

The on-again, off-again romance warmed up in 1967, at the same time Keser Israel was planning renovation of the sanctuary. Rabbi Klein met with Rabbi Ofseyer and they agreed on their respective duties in a merged group. Rabbi Klein was to assume emeritus status. Talks were again cancelled. The event that changed the hearts and minds of most of Keser Israel’s members was a most unfortunate one: Rabbi Andrew Klein passed away in July 1967.

Committees again worked out the final details such as memorials, constitution, cemeteries, board representation, etc. Each Keser Israel family taxed itself an amount based on the average Beth El contribution to the building fund. Chairman Alvin Mermin stated it beautifully in his report: “By so doing, we join the merged synagogue as equals, and with the unqualified privilege of becoming involved fully in its affairs and administration — for it indeed will belong to us, and our children, for many years to come — and with God’s help, may we all live to participate and enjoy it.”

Both Congregations voted approval of the merger on 31 March 1968. Commenting in 1985, Rabbi Elliot Gertel noted that “seventeen years having passed, all vestiges of ‘this group’ or ‘that group’ have disappeared and the best features of each have come forward in a truly melded congregation.”

The merged synagogues, called Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel, boasted in the fall of 1968 a membership of more than 600 families with more than 200 children in the Religious school. The fortunes of the times, however, ceased smiling. The City of New Haven hired a new Superintendent of schools who introduced a program of racial integration before it became a popular notion. For many years, Sheridan Junior High School in the Westville area, with a largely white student body, had a relatively high academic standing. Some of the Sheridan children were to be bused to other areas of the city. Many parents, including congregation members, feared that the admixture of their children with those from families they viewed as “less motivated” would lead to a decline in educational quality. They saw their choice as: leave town or send the children to a private school. Some left town, and the congregation. Others who left the city stayed with the congregation only until the children completed their studies in the Religious School. New Jewish families with young children avoided the city or sent their children to the Hebrew Day School (Orthodox) or Ezra Academy (Conservative). With the financial burdens of private school education, many families chose to avoid a synagogue commitment. By the late 1970s Beth El-Keser Israel membership was smaller and older.

During these challenging years, the synagogue enjoyed the leadership of dedicated members, including presidents Louis Goodwin z”l, Robert Shure z”l, Lawrence Garfinkel and Leon Rosoff z”l. See BEKI Religious School: A Handbook for Parents, Spring 1970-5730.

Paul Goodwin re-assumed the presidency in the years 1978 to 1980 with a specific goal: to engineer a merger with the Orange Synagogue Center. Orange had a substantial membership of young families but not enough room in their building for an adequate school or for social functions. BEKI had excellent facilities and was currently without a rabbi. The distance between the synagogues represented a 10- or 15-minute car ride.

An “engagement” for one year was arranged during which Shabbat services were held in alternate buildings. Beth El-Keser Israel easily contained both groups for the High Holidays. The Orange group really wanted a synagogue in their own backyard and contemplated ultimate sale of the BEKI building and new construction in Orange. The “marriage” never occurred.

Rabbi Elliot B. Gertel came to BEKI in the spring of 1982, as Dr. Alan Gelbert was concluding his term as president. With typical thoroughness he had surveyed the area and was convinced that there was a substantial number of uncommitted Jewish families who were potential members. People were also beginning to move back to the city, and Westville was still a good neighborhood in which to live. The congregation kept the dues low, with inducements for young families, but largely through the efforts of the Rabbi, some former resignees returned to the fold. The Rabbi also established the “BEKI Choir” in the fall of 1982 for Friday evening and other special services.

A jointly operated Hebrew School with Congregation Sinai, West Haven, was founded in the summer of 1983. By the fall of 1984, The Westville Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation, had joined the new United Hebrew School of Greater New Haven, a dream that was envisioned and discussed many years ago but never brought to life until then. Other congregations were invited to participate in this idea of creating a community-wide religious school. But no other congregations joined. Rabbi Gertel also fostered the establishment of a Hebrew School Endowment Fund. The interest on the fund is used to defray the costs of BEKI‘s expenses in operating the school, thus easing the burden on the synagogue’s general budget. Having a religious school once again was a major stimulus in developing young membership. Herbert Etkind served as president from 1983 to 1985.

But by 1996, due to declining demographic trends, Congregation Sinai withdrew from the School. In 2000, the School was dissolved, in part due the desire of some BEKI families to develop a school more closely integrated with the Congregation and more closely projecting its values as a traditional egalitarian Conservative synagogue.

Following Rabbi Gertel’s move to a larger and more prominent congregation in Chicago in 1988, Rabbi Steven Kane served the Congregation until 1993, at which time David Sagerman served as president. During those years, Rabbi Kane cultivated the Congregation’s appeal to traditionally observant Conservative Jews, and worked diligently to develop the Congregation’s membership and educational programs.

During the years following the merger, despite the continuing efforts of the synagogue leadership, the synagogue faced frequent budget shortfalls and was forced to defer certain building maintenance. While some positive movement was felt, the general trend of synagogue membership was down. By 1994, following Rabbi Kane’s departure, the Congregation’s membership stood at 204 families, the roof leaked, the parking lot had sinkholes, the heating and cooling plants were failing frequently, the carpets were tattered and the paint peeling. Some congregational leaders spoke of seeking merger partners or of ceasing operations.

In August 1993, Rabbi Jon-Jay Tilsen assumed the position of Spiritual Leader of the Congregation, with Milton Smirnoff (1993-1995) as President, as the Congregation began its second century.

During the ensuing decade, synagogue presidents including Saul Bell (1995-1997), Brian Karsif (1998-2001), Stephen Pincus (2001-2002), Gila Reinstein (2002-2004), Donna R. Levine (2005-2007), Dr. Jay Sokolow (2007-2011), Carole Bass (2011-2013), Nadav Sela (2013), Andrew Hirshfield (2013-2016) and Harold Birn (2016-) worked closely with the Rabbi to develop and implement a vision for the Congregation.

Rabbi Tilsen agreed with Rabbi Gertel’s assessment of the Congregation’s potential, and worked with synagogue leaders to further develop along the course suggested by Rabbis Gertel and Kane.

Louis Friedman z”l

In 1993, Mr. Louis Friedman z”l, whose birth predated the establishment of Congregation Bnai Israel, retired after over forty years as shamash. While rabbis had come and gone — several staying only six months to a year in the 1970s — the Rev. Louis Friedman served as an anchor of continuity for the community. His retirement necessitated the mobilization of volunteers to read Torah, lead daily and Shabbat services, teach benei mitzva students, and provide the many services so capably performed by Mr. Friedman. A wise, pious and humble scholar, Mr. Friedman raised generations of New Haven youth with a love of Torah. His commitment to tradition and the advancement of women eased the Congregation’s transition to a fully gender-egalitarian format in all aspects of synagogue life. A Sanctuary anteroom is named in his honor, and the Louis Friedman Scholarship Fund promotes youth education each year.

Several religious and educational initiatives were undertaken during the 1990s. The Kulanu Ke’Ehad program of outreach to adults with special needs relating to developmental disabilities was begun in 1997. Kulanu is supported in part by The David & Lillian Levine Endowment for People with Special Needs, which was established by the J. Paul Levine and Richard Levine Families, in memory of their parents David & Lillian Levine z”l. Through the generosity of Tina Rose and others, the Congregation retrofitted the main floor with an accessible washroom, as initial steps were taken to make the building more welcoming to everyone. The Congregation also undertook a commitment to offer a basic religious school education to all of its children whatever their special learning needs. In 2001, the Congregation received the coveted Solomon Schechter Gold Award from the United Synagogue for Conservative Judaism for its efforts in outreach and programming for people with special needs.

A weekly Rashi Study Group began reading the Five Books of Moses verse by verse in 1994, and by 2007 had reached the end of Numbers, and concluded I Samuel at Passover 2015. Several other weekly and occasional study groups formed or were developed during these years. The Shabbat Shalom Learners’ Minyan (later renamed “Shabbat Shalom Torah Study”), initiated in the 1980s, continued to attract a diverse and loyal following.

In 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 BEKI won Energy Star Awards and was designated an Energy Star Congregation by the United States Environmental Protection Agency of the Department of Energy in recognition of its efforts at energy conservation. In 2001, the Congregation received the coveted Solomon Schechter Gold Award from the United Synagogue for Conservative Judaism for its efforts in environmental stewardship. In 2006, the Congregation received a major grant from the Legacy Heritage Fund to further its efforts in family education and synagogue transformation through the issues related to solar energy and conservation. By 2016, most of the congregation’s electricity use was produced on its own roof-top arrays.

The breadth and quality of Shabbat and weekday programs for children and youth expanded, as the number of minors in the Congregation grew from under 70 in 1994 to over 225 a decade later. A typical Shabbat morning includes simultaneous programs or services for children and youth, as well as youth participating in the main service and Shabbat Shalom Torah Study.

George G. Posener with Leah z”l

A significant gift by Sara Oppenheim in 1994 began the Congregation’s slow “endowment campaign” with the establishment of The Morris & Sara Oppenheim Fund for Sacred Music. George G. Posener has been among the largest contributors to the Congregation’s endowment campaign as well as a distinguished leader. By 2009, following a major bequest by Irma Hamburger z”l (pictured below with Oscar Hamburger z”l), the Congregation’s endowments rose to over $2,000,000. While modest in comparison to the Synagogue’s needs, the establishment of these permanent funds represented a vote of confidence in the Congregation’s future, as well as a significant tool to help the Congregation achieve fiscal stability. Endowment income represents about 18% of the annual operating income.

In 2003, the Congregation began a process of building renovations, aimed at improving the accessibility of the building, enhancing energy efficiency, and upgrading security. John Weiser served as Renovations Committee chairperson. Phase I renovations (2003-2004) included replacing the main HVAC plant which dated from 1959. Phase II renovations (2005-2007) included replacing incandescent lighting with fluorescent lighting in the lobby and hallway areas, replacing incandescent exit signs with LED signs, insulating the lobby ceiling, replacing single-pane windows, adding window treatments, replacing fan coil “blower” units, installing zoned thermostatic controls, and adding bypass valves to eight major blower units in the sanctuary, social hall and lower social hall. A new accessible entryway was created; an elevator was installed; and handicapped washroom and nursing rooms were created adjacent to the newly-expanded lobby. The Claire Goodwin Youth Room was renovated and relocated to open to the courtyard; a new George G. Posener Daily Chapel and Rosenkrantz Family Library together serve as the beit midrash.

Irma (z”l) and Oscar (z”l) Hamburger

In May 2013, the lower level men’s washroom and women’s washroom and women’s lounge were updated to be fully accessible. The project included widening the doorways and installation of new fixtures. The project was sponsored by the BEKI Sisterhood, The Buckman Family and the Sachs Family. Also in 2013, two roof sections were replaced, and a major bequest was received from the estate of Ida Goldstein.

Well over three hundred families are now members of BEKI, and many more families consider it their spiritual home. Most of our members live in New Haven, and one exciting trend is the large group of members who have moved to the neighborhood of Westville to be close to, even within walking distance, of the shul. Many members also live in the downtown, East Rock, and Beaver Hills neighborhoods, as well as in numerous suburban towns. Many of our members are gerim, converts to Judaism (also known as Jews by choice), and many converted under the sponsorship of Rabbi Woodward. We welcome Jews in loving partnerships with non-Jews, and we consider it a core principle to be welcoming to all people.